Before the arrival of Europeans, what would eventually become Boston was basically two islands, connected to each other by a marsh, and connected to the mainland by a narrow strip of land. The larger "island" was known as the Shawmut Penninsula (where all of downtown Boston is today) and the smaller "island" was known as Copp's Hill (now the North End)

Some of the first expansion of land beyond the original shoreline of the Shawmut Penninsula (where the City of Boston was founded) occurred in what is now the central waterfront area (near the present Long Wharf area and the New England Aquarium). This was closely followed by land being added to what is now the Financial district.

For over 200 years, Boston was one of the busiest seaports on the East coast of what would eventually become the United States. Initially, the expansion of Boston's land into the ocean was done to facilitate the shipping industry. Wharves were created to make it easy to load and unload cargo from ever-increasingly large ships. At the same time, boats needed protected mooring areas (primarily to protect them from heavy weather and waves, but also to keep the ships safe from pirates, theives, enemy ships, etc.). Man-made inlets, then called "docks", were commonly created to keep boats safe.

One of the first public docks (remember that the word "dock" had a different meaning - it refers to an open water area where boats can be moored) was known as "Scottow's Dock" and it was created by digging out marshy land just north of the present-day Quincy Market/ Fanueil Hall area. Constructed in 1654, it was accessible via a drawbridge (on present-day North Street). The edge of what was Scottow's Dock, along Blackstone Street, is where Haymarket is found.

Filling and building proceeded. By 1827, you can see the entire Fanueil Hall/ Quincy Market market area at the edge of the ocean.

Much of the fill used to create the land over Scottow's Dock, and for the Fanueil Hall Area, was apparantly from trash collected from houses, taverns, and various craftsepeople.

Questions to Explore:

Using trash for fill was widely accepted until the late 1700's. Trash was very convenient. But, what are the drawbacks to using trash as fill material? What other alternatives can you think of to use instead of trash? What are the advantages and disadvantages of your alternatives?

1640's Map of Boston.

Looking down Blackstone Street. On the left was the locaton of Scottow's Dock, built on a marshy area known as Bellingham's Marsh.

This is the approximate location of the drawbridge for boats to gain access to Scottow's Dock in the late 1600's.

In the late 1600's, this would have been in the middle of Scottow's Dock.

If you stand in front of the Sam Adams statue just outside Fanueil Hall, you are standing on the location of the shoreline in the early 1600's. In the 1670's, land was created in this area and another public "dock", enclosed by land, was built. This dock was known as the "Town Dock". The Town Dock area was filled, in various stages, but remained in some form until it was completely filled in by 1784. Fanueil Hall was built in 1742 as a public market.

Questions to Explore:

Fanueil Hall and Quincy Market have been public markets since they were built in the 1700's. What about their location makes them so successful? Were the reasons the same in the past as they are now?

The Sam Adams Statue; just past the 1630's shoreline in the water. Good thing he's up on a pedestal (and that he wasn't born yet in 1630) or he'd have wet feet.

Looking up at Boston City Hall. If this structure existed in 1630, the mayor would have a waterfront view.

Etched into the stones on the Fanueil Hall plaza is the approximate location of the shoreline in 1630.

You can see the faint etching of the 1630's shoreline as you look back towards Congress Street.

Following the shoreline, you'll find several etchings of sea plants and animals.

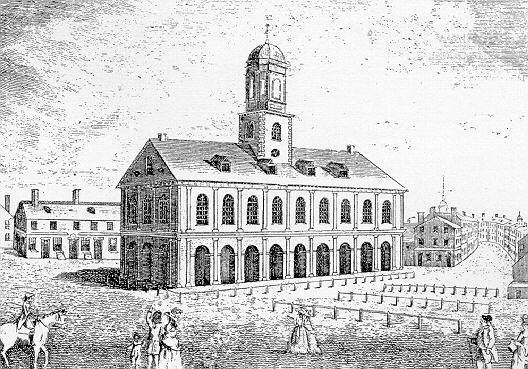

Fanueil Hall in 1789. Note fences for tying up your horse.

Faneuil Hall / Quincy Market in 1827

Faneuil Hall / Quincy Market in 2009

(Note that this Fort Hill is not the one that exists in Roxbury. In fact, the Fort Hill described below no longer exists!)

Fort Hill was a classic example of how land was used and then destroyed to make way for new projects. Some might call this Boston's first "urban renewal" project!

Fort Hill was the most southern of the original hills on the Shawmut Penninsula. Because of its commanding presence over the harbor, it had a fort built on it. After the Revolution, it became a desirable place to live, and wealthy people, involved in the shipping industry, built fancy homes there. In the 1820's and 1830's these wealthy people moved away to other neighborhoods. Institutions (such as the Perkins School for the Blind) acquired these buildings. Unfortunately these institutions then left as well, and by the 1840's Fort Hill became a poor neighborhood for Irish immigrants (who were fleeing the Irish potato famine to Boston at that time). The neighborhood became overcrowded and unhealthy (laregely due to the actions of irresponsible absentee landlords). For example, some people found themselves living in apartments with no ventilation and open sewage draining into their dwellings. These conditions helped lead to a cholera epidemic in 1849.

A proposal was put forth in 1854 to create land for exanding businesses along the waterfront. The businessmen who proposed this idea suggested cutting down Fort Hill and using it to fill in more of the waterfront (in the present Atlantic Avenue area). At first, the city simply tried to cut through the middle of the hill along Oliver Street, but when the hillsides began to collapse, they tore the whole hill down and used the material as land fill.

Map from late 1600's showing the location of Fort Hill. Note that there is actually a fort on the hill.

Oliver Street under construction in 1867.

Oliver Street in 2009 - this photo was taken from the same location as the one to the left. Click on this image to get a sense of where the bridge would be if it were around today...

Questions to Explore:

The Oliver Street project failed because after they excavated through Fort Hill, the sides of the excavation collapsed onto the roadway. Can you explain why the sides collapsed?

Imagine you were an engineer hired to oversee this project. How would you recommend the excavation be done in a way that would prevent the collapse of the hill? What reasons can you think of why your ideas (and others like them) were not used in 1867?

Creating land along what is now Atlantic Avenue. Fort Hill is being torn down to use as fill for this project.

Tearing down Fort Hill, which was collapsing after the construction of Oliver Street in 1867.

Questions to Explore:

Boston has demolished and then rebuilt neighborhoods several times in its history. What happens to people who live in the neighborhood when it is torn down and transformed?

If you were in a position of power in Boston when Fort Hill was being excavated, what solutions might you suggest to provide housing for those who lived on the hill?

Where do you think the Irish immigrants who lived on Fort Hill ended up moving to? (Hint: Where is Boston's biggest Saint Patrick's Day Parade held to this day?)

International Place, Fort Hill Square, in 2009. This was the location of the summit of Fort Hill, which was about 40 feet higher than today's ground (about the height of the first full row of windows on the right hand building.

This was once the location of Half Moon Place, which was an area with some of the worst conditions on Fort Hill - a 1849 cholera epidemic was centered here.

The project that created the present shoreline along the waterfront area was the creation of Atlantic Avenue between 1869 and 1872. Partly as an excuse to tear down the slums of Fort Hill, and partly to facilitate the transportation, by rail, of goods from the southern part of the city to the north, this project was undertaken.

The shortest railroad pathway from the rail terminal in the southern part of the city (near present-day South Station) to the north (near present-day North Station), was across the wharves along the waterfront. To make this project happen, areas between existing wharf areas were filled and several buildings were literally chopped in two! As mentioned above, the fill for this project came from Fort Hill.

Questions to Explore:

Look carefully at the two photos below, that are at least 50 years apart. What has changed in the intervening years? In what ways is the waterfont land being used differently in the two pictures?

Atlantic Ave, showing the train line whose construction required the splitting of existing buildings. The Commercial Wharf Building, seen as the first line of wharf buildings in this photo, can be seen today in the picture below.

This shows Christopher Columbus park. At the edge of the park, right along the water, is where the old Atlantic Avenue was located (it has since been moved to the left side of the park). The old Atlantic Avenue is where the train once ran from North Station to South Station.

Also, you can see the Commercial Wharf Building (the grey building in the middle of the picture) which had been split to allow construction of the old Atlantic Avenue.

Atlantic Ave, 1900

The re-routed Altantic Avenue 2009, looking North.