The story of land making in Boston's Back Bay has several chapters.

Creating land below Beacon Hill and creating the Public Gardens

The Mill Dam Project and creating the land in the rest of Back Bay

Boston map from the 1640's.

Map of present-day downtown Boston. Click on the map to see the present-day map with the 1640's map overlaid.

Questions to Explore:

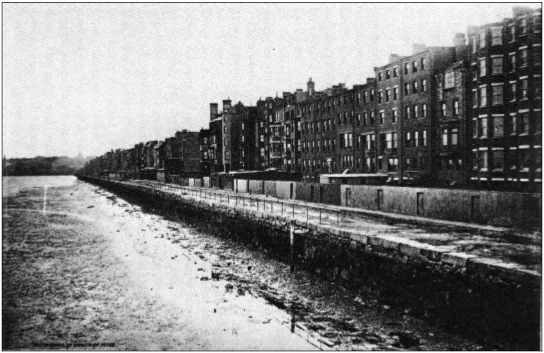

The photograph on the left shows a tidal bay at low tide, when the mud flats are visible. This is probably what it looked like in Back Bay (at low tide) when Europeans first arrived in Boston. (In fact, this bay is only about 1/2 the size of Back Bay!).

It can't have been easy to turn this into dry land. Why do you think Boston decided to do it?

What do you think some of the challenges would be in undertaking such a project?

What would you fill this area with to create new dry land? How would you move the fill material into the bay?

Read on to discover the story of how and Back Bay was turned into land.

Filling in below Beacon Hill and creating the Public Gardens

The first chapter in the filling of Back Bay was the filling of a strip along the eastern section of the bay starting in 1804, and the creation of the Public Gardens and a section of Beacon Hill (along the river) in 1837. Boston had been using the area as a trash dump, and citizens were complaining about the stench (and pests). Boston's solution was to completely fill its portion of the Back Bay mud flats. The fill for this came from the west peak of Beacon Hill (known as Mount Vernon).

Question to Explore:

What about Beacon Hill made it a good source of fill material? (Need a hint? Click here to read about glacial geology.)

View looking down Charles Street from the intersection of Charles and Beacon Streets. This was roughly the location of original shoreline from the time that Europeans settled the area until the 1830's.

Map of Boston from 1826. Note the location of the shoreline, on the west edge of Boston Common.

Cutting down of Beacon Hill to fill in the eastern edge of Back Bay, including the Public Gardens. This picture is from ~1810-1811.

The intersection of Charles and Beacon Streets. Imagine standing on this spot in 1800 - you'd be standing in a tidal bay looking at the shore!

Looking up Beacon Street towards the State House. Again, if this were 1800, you'd be looking up at the shore!

A view of the Public Gardens from Arlington Street. This was land created in 1837; before that it would have been under water!

Another picture fron the Public Gardens. (Note the inscription on the statue: "Cast thy bread upon the waters". Prior to 1837, if you were standing here, you would be able to do so directly into the bay!)

The second chapter in Back Bay's story involved the "Mill Dam Project." In the early 1800's, cities were growing because of new industries that relied on water power. Most, such as Waltham, Lowell and Lawrence, had rivers whose energy could be tapped to power mills. These mills were used for many things, including grinding grain, cutting wood and metal, and manufacturing cloth. Boston was at a disadvantage - the Charles River moved too slowly by the time it reached Boston. In addition, because it was an estuary, its direction of flow would literally change between high tide and low tide.

Boston industrialists proposed using the power of the tides to drive mills instead. One mill dam had already been built in the 1700's and worked well for many years. (This project involved a dam between what is now the North End and the former West End.)

The Mill Dam Project was a failed attempt to generate power for manufacturing using the ten-foot tides in the Charles River as a power source. It was constructed from 1818 to 1821 and is an interesting example of using a renewable resource, but one that was ultimately unsuccessful (due to the fact that the dams themselves interfered with the action of the tides).

For more information about Tide Mills:

- What is a Tide Mill?

- Tide Mills along coastal Maine

- Modern uses of Tidal Power for Electricity Generation

- Short overview of Tidal Power, including a discussion of environmental hazards

An early English tide mill

Questions to Explore:

Consider the movement of water as a result of tides. In Boston, the tide rises about 10 feet between low and high tide. How might this power be harnessed effectively?

What additional challenges exist in building a tidal-powered mill as opposed to a river-powered mill?

Thought Experiment: Propose a design that would use the power of the tides to drive a mill.

The City of Boston approved this project, and in 1821 the Back Bay Mill Dam was completed. Unfortunately, this project was a failure. In addition to not producing the expected power for the number of mills predicted (only 3 were ever in operation at one time; 81 were predicted!), the damming of Back Bay prevented the flushing of sewage and trash out to sea.

The dam created a stagnant lagoon that was often drained completely. It was the practice for Bostonians to dump raw sewage and trash directly into the ocean. Ordinarily the tidal action of the bay would at least wash much of this waste out to sea. By damming up the Back Bay, this tidal flushing was stopped. Imagine the incredible stench that must have built up, particularly on those hot and sticky summer Boston afternoons! Not only that, this stagnant water became a breeding ground for hordes of mosquitoes!Foul odors and increased mosquitos (and other pests) were the ultimate product of the Mill Dam Project.

Boston was also facing population pressures in the mid-1800's, so there was a great deal of popular support for the idea of filling in Back Bay to create land for more housing.

While filling in of this large area was in itself a complex project, this was made more complicated by the fact that control over the Back Bay tidal flats was divided up between the State and two different corporations. It took over 4 years for these groups to work out an agreement as to how to divide up the project of filling in the mud flats.

There is no remaining evidence of the Mill Dam visible at the surface, but you can walk along the top of what was once the dam, by walking down Beacon Street! If you start at the foot of Beacon Hill and walk down Beacon Street all the way to Kenmore Square, you will have traversed the entire length of the dam. (Yes, it was a long dam!)

Photograph from the State House, towards Back Bay, showing the Mill Dam. When do you think this photo was taken? What clues can you use to determine the age of the photo?

Map of the Back Bay in 1836, showing the Mill Dam crossing the top of the Bay. You can see the Public Gardens just below the dam on its right.

Looking at the Public Gardens across Arlington Street. Between 1810 and the 1850's, you'd be standing in the Bay looking at the shore!

A view down Beacon Street. Standing here in the mid-1800's, you'd be standing on the end of a long dam running across a tidal bay. This dam stretched from this location (the corner of Beacon and Charles) all the way over to Kenmore Square.

Two houses built ~1850 (93-94 Beacon Street). These houses, along with several others, were built directly on top of the Mill Dam itself.

Arlington Street Church under construction. This is at the corner of Arlington and Boylston Streets. You can see the fence at the edge of the Public Gardens in the lower right hand corner. (1860's)

Modern picture of the Arlington Street Church (corner of Arlington and Boylston Streets).

Construction of Commonwealth Avenue. (Late 1860's)

The mall that runs down Commonwealth Avenue today (2009)

Copley Square, corner of Dartmouth and Boylston Street. (1880's)

Copley Square, today.

Museum of Natural History (now Louis of Boston). Corner of Berkeley and Newbury Streets

The same structure today.

Questions to Explore:

Why Needham? Needham provided a nearby source of inexpensive gravel and sand. Several hills were destroyed to move all this material into Boston! Why did Neeham have so much of this material? Glaciers! For More information, see "Glaciers in Boston"

A steam shovel digging out gravel in Needham (~1860's).

A gravel train in a Needham gravel pit (~1860's)

A modern-day gravel pit formed by glacial action.

Today the Esplanade is one of Boston's premier parks. It stretches along the Charles River, from the Science Museum for three miles upstream. Originally, Francis Law Olmstead designed this park as part of a large network of parks in Boston known as the "Emerald Necklace". Residents of early Back Bay could walk from their homes to the peaceful banks of the Charles River.

Now, the Esplanade is somewhat cut off from the rest of the city by the Storrow Drive highway. Built in the early 1950's, parts of Storrow Drive is now in need of major repair. Many feel that Storrow Drive should be dismantled, and the original beauty of Olmstead's park restored. Others disagree.

Question to Explore:

Why do you think there is so much disagreement over what to do with Storrow Drive? Put yourself in the shoes of people who might feel strongly on either side of this issue - what arguments might they make?

Can you think of a creative solution that might preserve the highway and bring back more of the beauty of the park? What challenges would you face in implementing your solution - think from the perspective of an engineer?

The filling of the entire area took until the late 1880's. The Fenway area didn't get filled until 1900. The Esplanade (along Charles River) was initially completed in 1909, widened in the 1930's, and then widened again in the 1950's (when Storrow Drive was put in). The main reason it took so long was the incredible expense of filling in this land.

The bank of the Charles River along Back Bay, just before the Esplanade was constructed. The seawall was covered over when the Esplanade was built in the 1890's, but when Storrow Drive was built in 1951, parts of the seawall were then uncovered.

The Esplanade as it looked in the 1920's.

The Esplanade in the 1930's. In the 1930's, the park was widened and artificial lagoons constructed to promote boating.

Questions to Explore:

Unlike most of the rest of Back Bay, the fill that was used to create the Esplanade came from dredging the Charles River.

What are the challenges in digging up a riverbed and using that material for fill?

View overlooking Storrow Drive from the Dartmouth Street footbridge. The rock wall you see at the edge of the highway is actually part of the seawall built in the 1860's. In the 1860's this rock wall was the extent of the land.

Closeup of the 1860's seawall

View over Storrow Drive today. Click on the photo to see the extent of the land in the 1860's, 1910's, and 1930's.

Want to know more?

- For an excellent radio story about what to do with Storrow Drive, click to listen to "Radio Boston" from July 2009.